Climate change, the countryside and CPRE

Dame Fiona Reynolds looks back at CPRE’s long history of pushing for climate action and asks if the countryside itself is our secret weapon against global warming.

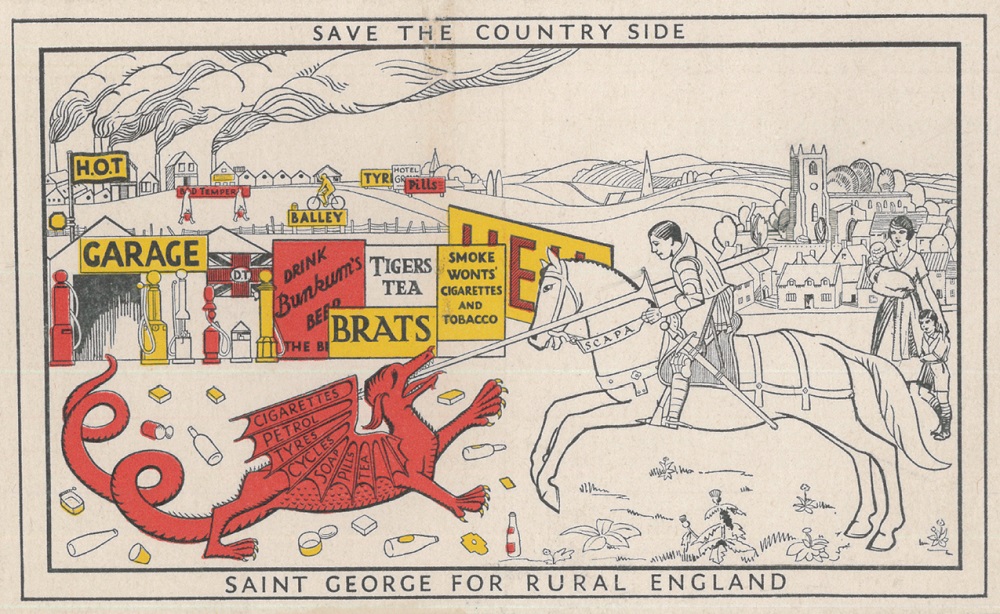

From its foundation in 1926, CPRE rapidly became known for its expertise and effectiveness on planning issues – raising awareness of the blighting of beautiful countryside by urban sprawl, and building political alliances to restrict ‘ribbon development’ and control development outside cities.

But the controversy into which I entered in the early 1980s raised new challenges. CPRE was again a whistleblower, this time calling out the damage being done to the countryside by agricultural intensification; a process which saw us switch from being the farmer’s friend (historically there was much to unite CPRE and farmers in saving good agricultural land from development) to first-class awkward.

CPRE and farming

Chief of the awkward squad was Marion Shoard, Assistant Secretary of CPRE when I arrived as Secretary of the Council (now Campaign) for National Parks in 1980. Her book The Theft of the Countryside told an excoriating and hitherto unexposed tale of damage to wildlife and the landscape, mostly as a result of subsidised farm improvements. Her analysis was not challenged, but it was a tough message and not one that people were used to hearing from CPRE. Some farmers recognised that things had to change, but it was a controversial and difficult time. More than once I remember being told that we should ‘stick to our knitting’ (ie planning work) and stop meddling in things that weren’t our business.

But of course for a charity that cares about the countryside, farming had to be our business. And so CPRE was not only right to object to the damage but also to focus quickly on finding new and better ways of funding farming. I was part of the small CPRE-led team that succeeded in persuading the UK government to stop giving grants for tearing out hedgerows and ponds, and for European Commission consent for agricultural subsidies to be switched towards conservation-friendly farming, first in designated Environmentally Sensitive Areas; later across the wider countryside. The shift was small scale at first but our arguments gathered momentum. It’s now accepted wisdom that public funds should deliver public benefits, even though we are a long way from this promise being delivered.

Countryside campaigning

And of course, farming was far from our only sphere of campaigning. In the 1980s and 90s CPRE was deeply engaged in policy debates and campaigns against ugly roads, power stations and quarries, as well as protecting the Green Belt and objecting to speculative greenfield housing developments. Only rarely did we oppose development outright; our questions were often ‘why here?’; ‘why so big?’; ‘couldn’t we achieve the objective another way?’.

And naturally, the means of influencing such projects was via planning or planning-type processes in which CPRE had unrivalled expertise. But there were strong themes to our work which in retrospect seem prescient: a focus on energy conservation to reduce the need for new power stations, traffic management rather than providing new roads and investing in urban regeneration and the reuse of brownfield sites to improve the quality of city life and take pressure off the countryside.

Climate emergency

When, in the 1980s, we began to hear about the phenomenon of climate change, it was logical to apply the same principles to this issue. Though the evidence was contested by some, there was never any doubt that the countryside would both be affected and part of the solution to climate change. We saw clear links with our work on energy and transport, conscious of the car-dependent, wasteful energy uses created by huge greenfield housing estates and out of town shopping centres. And we began to explore how farming and land use might need to respond to a changing climate. From the start, we were engaged in the issues.

Today the case for CPRE’s leadership is even more urgent. The evidence is not just clear, it is accepted by both the scientific and political communities and there are increasingly ambitious commitments to act at both domestic and international levels. One of Theresa May’s last decisions as Prime Minister was that the UK would achieve net-zero carbon by 2050, putting us in the vanguard internationally. It also puts us on our mettle, for we are far from on target to achieve this goal.

Now everyone is talking about the climate crisis and demanding action. The pace and scale of extreme weather disruption are more intense than many predicted, and we know we must keep temperature increases to less than 1.5C degrees. To achieve that we must not only radically reduce carbon dioxide emissions into the atmosphere, but also restore the valuable carbon sinks we have treated so cavalierly, and manage land and our demands on it in truly sustainable ways. This means that landscapes must and will change: to hold carbon, to increase tree cover, provide new sources of green energy and help us live more sustainably as a society.

The role of CPRE

Some of these demands will present challenges for CPRE, but many will present opportunities. CPRE should be in the vanguard of guiding change in ways that respect and enhance what we already love, and working to create new beauty, just as it has before.

To do that, CPRE will need to harness allies and inspire people, just as it did in the 1920s. At present climate change too often inspires confusion, anger and fear. It can seem distant and technical (talk of carbon budgets, emissions control and atmospheric concentrations leave many people cold), far removed from the task of protecting the countryside we love.

So our response must be human, optimistic and achievable. For we can make a difference, both in our own lives and as part of a bigger societal response. And the countryside can make a huge contribution to getting us onto a better trajectory.

Take farming. Three things would make a huge and lasting difference. First, restoring the carbon content of soils – especially peat – which has been so undermined by intensive farming. Second, planting millions more trees (including in towns and cities) and woodlands. And third, ensuring farming delivers public benefits along with food production that enables healthy, affordable diets for everyone. And it should not be a penance to eat more fruit, nuts and vegetables, consume less but well-produced meat and waste less food.

Planning ahead

The same is true when it comes to the pattern of future development, where CPRE’s expertise in planning and development will be needed to help provide solutions. To achieve net-zero, we need places that are good and healthy to live in, where we aren’t dependent on cars for everything we do and where longer journeys are increasingly possible by train.

We need to use land more efficiently, which means an increasing focus on urban renewal and recycling previously used land; and ensure everyone has access to green space and nature. And as individuals we’ll find alternatives to driving cars (which will increasingly be electric), walking and cycling where possible, not least for our physical and mental wellbeing. And here too we can see changes already happening. Many young people don’t expect to own a car, as car-sharing schemes and new technologies make alternatives increasingly feasible and attractive.

The principles behind these policies are increasingly uncontentious. They are also completely compatible with plans for nature recovery, another urgent goal. We just need to make them happen, and CPRE is well placed to help.

Inspiring change

As I write, there’s a risk it all sounds easier than it will prove to be, as there’ll inevitably be real tensions and choices we must all face. But unless we have an optimistic message I believe we won’t inspire people to act, or encourage a future that is governed more by aspirations for quality of life than material growth.

And that’s why I like to talk about beauty as an idea we might all be inspired to embrace. Beauty inspired and united the early CPRE campaigners and their allies, but even then it was never just about aesthetics. It was about the ‘right use of land’ (to quote a CPRE-influenced Government White Paper of 1944), a better future for everyone, good places to live and a beautiful, thriving countryside.

And if we are to deliver such a vision, we need to use language and images that inspire and resonate with people. I am fond of quoting Oliver Letwin’s lament in 2005 that:

… discussion of the environment has remained resolutely mechanical. There is the science of far-off events – admittedly of colossal significance, but none the less technical for that … the language of politics needs to reflect the felt experience of the environment as sensations and impressions that are capable of moving us to delight and awe … we need to conduct politics as if beauty matters.

We do. And if we do, I believe we will unite the people of Britain, just as CPRE has done in the past. Today’s challenge of climate change is bigger, but at its root is the same need to protect the places we love and the resources we depend on, to live in ways that respect them, and to plan to ensure a better, beautiful and long term future for ourselves and generations yet to come.

Fiona was Secretary to the Council for National Parks from 1980-87; worked for CPRE from 1987-1998, and was Director from 1992-98; and Director-General of the National Trust from 2000-2012. Her book The Fight for Beauty was published in 2016.